Recently, I had the chance to return to Wendell Berry’s “An Entrance to the Woods,” a favorite of mine for many reasons—an easily grasped example of the personal essay that combines present narrative action and meaningful reflection; an essay that knows its setting intimately and expertly; a pleasing blend of authority and pensiveness—but the piece of it that has stuck with me most since the first time I encountered it in the first creative nonfiction class I ever took, circa 2003, is this:

Once off the freeway, my pace gradually slowed, as the roads became progressively more primitive, from seventy miles an hour to a walk. And now, here at my camping place, I have stopped altogether. But my mind is still keyed to seventy miles an hour. And having come here so fast, it is still busy with the work I am usually doing. Having come here by the freeway, my mind is not so fully here as it would have been if I had come by the crookeder, slower state roads; it is incalculably farther away than it would have been if I had come all the way on foot, as my earliest predecessors came.

Berry is specifically referring to the process of traveling through physical space, and every time I travel somewhere, I feel the detachment he describes, the strange confusion of body and mind finding itself somewhere new in such an abrupt way. This, perhaps, is why a flight is both tiring and confusing at a cellular level, even though I’m not doing anything but sitting, reading, napping.

Today, though, I’m thinking of that pace in a different way: the distance in time and subject matter I find myself traveling from hour to hour as the semester careens through its third week. It’s a busy term: I’m teaching four different classes, which means four different preps, plus an independent study. On a typical Wednesday, I voyage from the Adriatic Sea in the early 17th century (my own writing) to 20th century baseball writing in America (sophomore lit class) to the European Middle Ages (first-year writing) to the 19th century British Empire (lit survey) to retellings of Greek mythology (independent study), with a little break for office hours and lunch. Same thing happens on Monday and Friday, minus the deities. On Tuesday and Thursday, it’s time for creative writing.

For me, semesters like these are more the rule than the exception; that’s part and parcel of teaching at a liberal arts college, and I quite enjoy being able to teach widely across my interests. I will not deny, however, that with each passing year, slingshotting myself across centuries and disciplines in the ten-minute transition between class meetings (while also bolting some water and triaging my inbox) seems to accumulate a certain kind of fatigue. As Berry says, my mind is still busy. Nevermind everything intruding past and through the coursework—my mind wants to still be busy with the material it has just spent fifty minutes discussing with interesting people. There could be notes to make, references to investigate, but instead there’s the incoming class to greet, those little messages to fling into the ether so they can’t intrude on more “useful” blocks of time later, some new time and place and subject whose doors I have to run through on the hour.

I’ve dabbled in all the possible variations and adjustments available for my schedule and dreamed of the impossible ones (where there are simply fewer numbers of things I’m responsible for). Given the parameters of my professional reality, there isn’t a way to change the metaphorical balance sheet of it all; that isn’t what I’m thinking about right now, anyway. I’m thinking about transitions, and how we move ourselves and our attention from one thing to another—not in that frantic algorithmic way that tugs at us, but across the eras of our days. While you might not be skimming centuries and continents in your morning, you might be juggling roles, managed to managing, planning for the future and attending to the urgent present, and those shifts take up their own space. Whether we have space to give them, whether we have any options to make space, they take it all the same.

What I’m making: First Breakfast Balls

I’m a dedicated two-breakfast person: one little something to buoy me through the writing time and then something more substantial before the teaching starts or after bouts on the bike, depending on the day. I have made many variations of Bikepacking’s Low-Waste Energy Balls, and these are one of my absolute favorite First Breakfasts because they’re wonderfully customizable. As long as your proportions are very roughly the same (one cup of dates or other sticky dried fruit, 2/3 c oats, 1/3-1/2 c. tasty mix-ins, 3 tbsp some kind of nut/seed butter), they turn out great. The current iteration has almond butter and some speculoos spread, plus hemp seeds, flax seeds, and cashews for texture, to go with the dates & oats core. One batch lasts me about a week if they stay designated as First Breakfast and not Afternoon Distraction. They keep in the fridge for that long, easily.

What I’m reading: Maybe it’s related to the heart of this newsletter this week, but even my reading is a little scattered. I’ve got more than half a dozen books with active bookmarks in them at the moment, not counting the ones I’m re-reading for class preps. The most recent of these indulgent dabbles is with Guy Gavriel Kay’s newest, All the Seas of the World. I’ve never read any GGK before, though people have been telling me to do so for years, so when I was at the library to pick up something else entirely and there it was, looking exceptionally pretty and engrossingly large, it wasn’t hard to bring it to the circ desk, too. So far, the characters have revealed themselves much more slowly than I expected, but the world feels appreciably layered and the characters I have met have complicated and spiky inner lives, which should lead somewher satisfying.

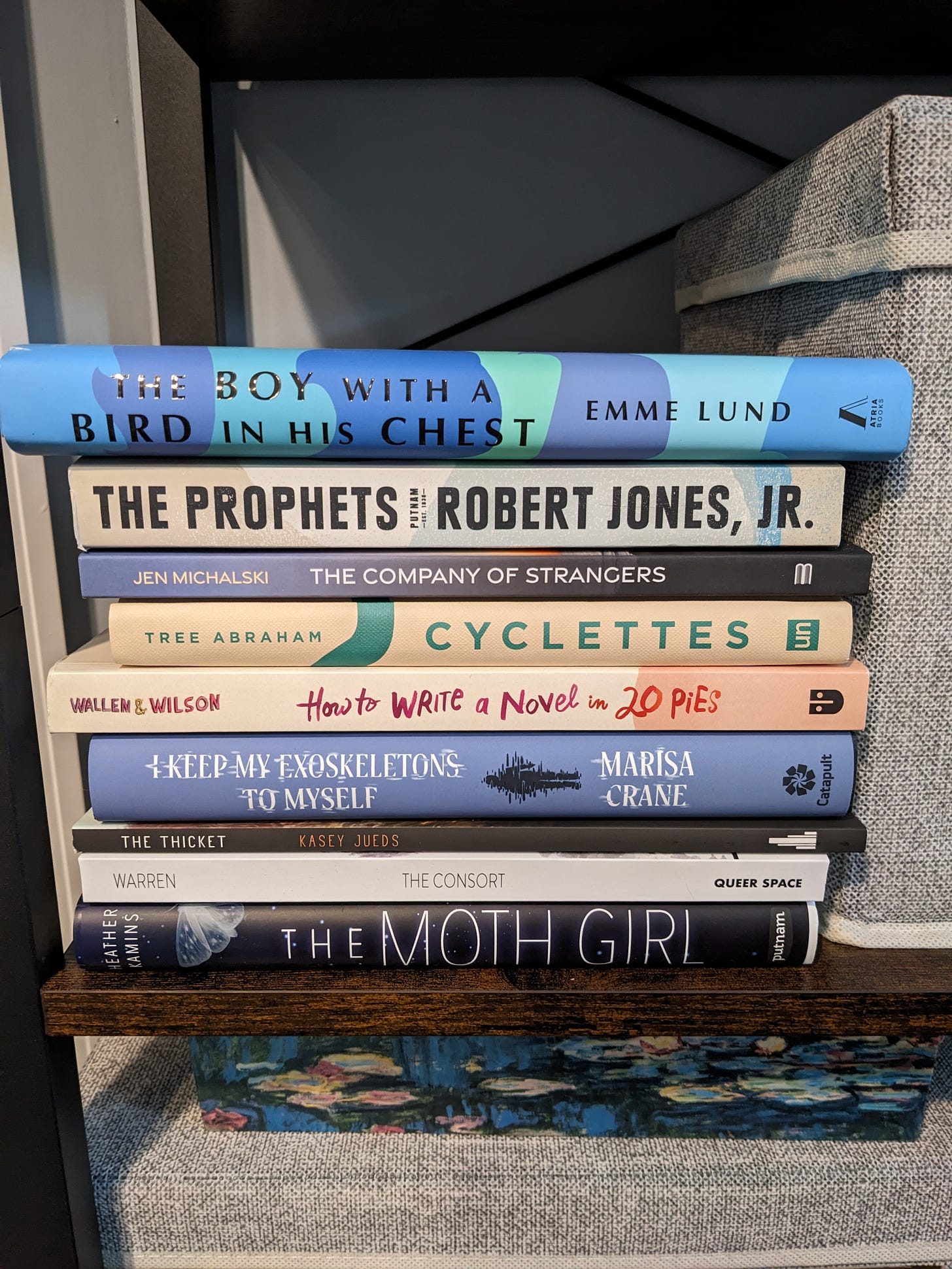

And the Book Fairies keep bringing new treasures. Take a peek at my non-exhaustive “I don’t know when, but please, God, soon” stack:

What I’m writing: I’m chipping away at this revision. I like to think I’m onto mostly the smaller chisels now.